The Seduction of Certainty

This recent video by science communicator and Veritasium host, Derek Muller, got me thinking about the role of confidence in leadership. In Muller’s telling, a trader—smart but prone to over-confidence and hiding his errors—watched his $40,000 loss turn into $1.3B, all by trusting his instincts and belief he could feel patterns others couldn’t.

It’s a familiar rhythm. People drift into overconfidence not out of arrogance but out of fear of incompetence. Not knowing. As studies have repeatedly shown, people who project confidence in times of uncertainty tend to be designated as leaders by the very people they mislead. Then the ground shifts and what once felt like leadership reveals itself as something quite fragile.

The Science Behind Overconfidence

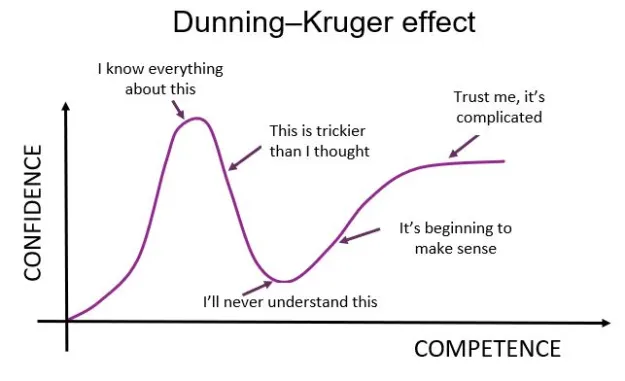

The cognitive bias that describes the systematic tendency of people with low ability in a specific area to give overly positive assessments of this ability is known as the Dunning–Kruger effect. The Dunning–Kruger effect has been demonstrated in a wide range of fields, from politics, medicine, driving, aviation, spatial memory, academics and, yes, business leadership.

While the following chart is a meme unreflective of the original studies, it gives you the gist of the effect: we aren’t as calibrated as we think we are.

The Identity Work of Confidence

The Space Shuttle Challenger story from the same video echoes this pattern. Engineers raised concerns. Data was incomplete. Leaders faced pressure. NASA relied on a culture of certainty that had become part of its identity at the time. And with that, the shuttle launched.

The trader collapsed not because he lacked skill, but because his adaptability froze in a sea of confidence.

NASA managers didn’t proceed out of recklessness. They proceeded because authority had trained them to treat certainty as competence.

Confidence didn’t enter the room as a villain. It entered as necessity. As reassurance. As the emotional glue holding things together under strain.

Leadership versus Authority: Why Certainty Feels Safer Than Truth

In organizations, this pattern shows up in quieter ways. A team insists it’s aligned because no one speaks up. A leader assumes she understands another division’s motivations. A department relies on its old success model even though the environment has already reconfigured itself. Confidence fills the room.

There is a kind of tightening that happens when we “know.” The breath shortens. Our attention collapses around the story that feels most familiar. Imagination narrows.

As former colleague Ron Heifetz likes to say, “We check our brains at the door and start acting stupider than we actually are.”

Reality stays outside the door, and stupidity enters unimpeded.

In adaptive leadership, this trap sits right at the fault line between leadership and authority. Authority thrives on projecting clarity. It leans heavily on the performance of certainty. It steadies the room. People look to it for direction, protection, order and expertise.

Those functions are essential. At their best in uncertain times, they stabilize the system long enough for adaptive work to happen.

Confidence Without Pretending

There is another form of confidence—one that doesn’t come from expertise or mastery. It comes from learning how to navigate uncertainty without losing your footing. It is quieter. Less performative. More rooted.

Technical confidence says “I know what to do.”

Adaptive confidence says “I know how to walk the terrain even when the path isn’t clear.”

The first compresses the field of vision. The second expands it.

People feel this deeper confidence. They sense when a leader is grounded even while acknowledging ambiguity. That steadiness becomes its own kind of leadership capital. It tells people that uncertainty is not a danger zone, but a space where new information can actually reach them.

This kind of confidence doesn’t pretend to know. It trusts the collective capacity to learn.

And learning is precisely what is required of adaptive challenges. Learning to renegotiate beliefs, expectations and deeply held identities.

In those moments when authority’s instinct is to reassure, leadership initiates learning by naming what isn’t clear. Leadership disturbs the water just enough that people can see what they couldn’t see before. Leadership steps into that gap. Not by discarding authority but by expanding the emotional range of what’s possible.

Leadership says let’s widen the frame. Let’s look again. Let’s create enough heat that people begin to see what they’ve been avoiding.

Leadership is not allergic to confidence. It is allergic to unwarranted certainty.

The Societal Cost of Certainty

The same dynamic that blinds organizations blinds societies.

The stories from the video reveal what happens when confidence outruns reality. People crave stability. They attach to familiar narratives. They move toward coherence even when the system they’re in is sending contradictory signals.

Even now, the gradual decline into authoritarianism, a topic I wrote about in Your Leadership Moment: Democratizing Leadership in an Age of Authoritarianism, can be partially attributed to our willingness to check our smarts at the door and usher political authoritarianism into office – left and right, for that matter.

The costs accumulate quietly:

- Signals get ignored

- People stop offering dissent

- Early warnings go unfelt

- Complexity gets pushed out of the frame

- The system drifts toward brittleness

- Brittleness becomes fear

- Fear becomes anger

- Anger becomes violence

The antidote is more honesty than confidence, more curiosity than decisiveness, more leadership than authority. More moments of true leadership, regardless of your formal authority.

Practices for Moving Through the Unknown

Adaptive leadership offers a different posture. Not self-doubt or paralysis, but something sturdier. A willingness to engage reality even when the picture is incomplete.

1. Make uncertainty discussable

Name what is unclear. Name what feels off. Name what hasn’t been said. The moment uncertainty becomes speakable, the system begins to breathe again.

2. Generate heat with purpose

Not pressure for its own sake. Just enough disequilibrium for people to see new patterns, examine assumptions, and let old narratives loosen their grip.

3. Treat strategies as hypotheses

Run experiments. Small ones. Frequent ones. Experiments keep the system honest. They protect against the kind of catastrophic overconfidence that took the trader down.

4. Widen interpretation

Invite people who see differently. People with dissenting views. People whose vantage point complicates the dominant narrative. This dissolves the illusion of understanding faster than any diagram.

5. Slow the rush to coherence

Coherence feels good. But premature coherence is usually a sign that complexity has been simplified out of existence. Let the picture remain blurry a little longer.

These aren’t mechanical tools. They’re forms of attention, which is one reason we emphasize attention in our leadership programs.

In nearly every situation, what you choose to attend to may in fact be the first and most consequential decision you make.

Seeing More Clearly: The Real Work of Leadership

One reason science channels like Veritasium and 3Blue1Brown resonate with me is that they reveal how much more there is to learn. They allow me to experience the liberation of updating my understanding and discarding old preferences and biases.

Good science and good adaptive leadership share the same ethic:

Stay curious.

Test assumptions.

Revise your models.

Speak honestly about limits.

Invite others into interpretation.

Release the old story when the evidence shifts.

Adaptive leadership is a discipline of seeing. Seeing people. Seeing dynamics. Seeing yourself. Seeing the parts of the system that authority would rather keep quiet. Seeing where confidence serves and where it distorts.

Leadership is not the assertion “I know.”

It’s the grounded willingness to see more clearly than the system is comfortable seeing.

When leaders embody that willingness, something subtle shifts.

People around them begin to relax into honesty. They name what’s been avoided. They acknowledge uncertainty without shame. They engage the work with a steadier heart.

Because the unknown is not the enemy. It’s the doorway.